gyapjú, 65×50 cm, digitális print papíron, A5, 2021

/ Wool 65×50 cm, digital print on paper, 2021

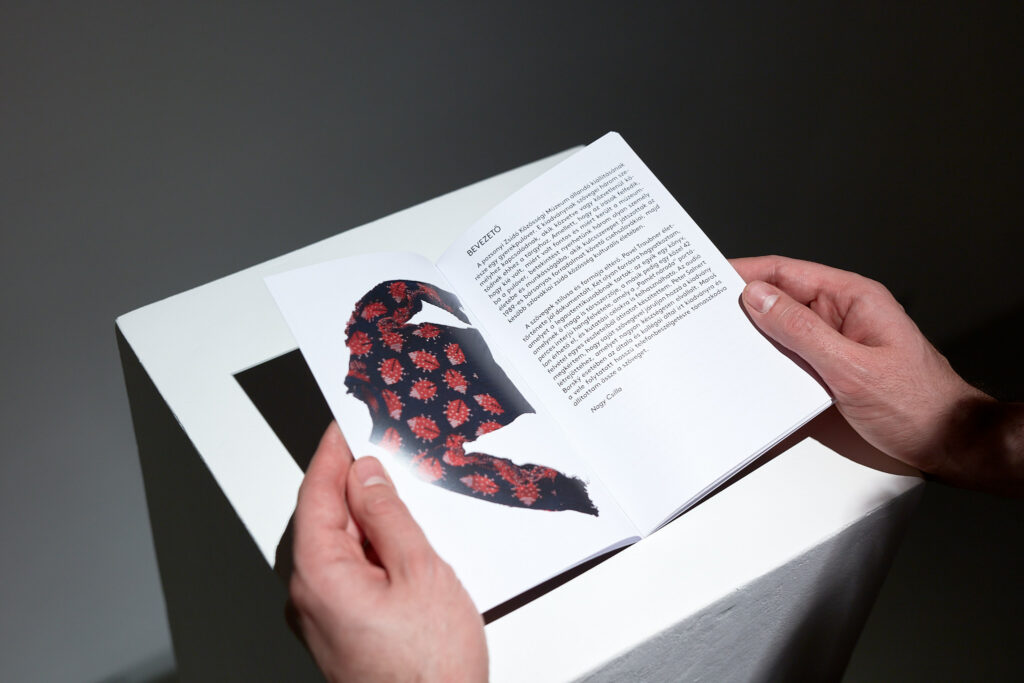

„A pozsonyi Zsidó Közösségi Múzeumban, a kiállított tárgyak közt szerepel egy gyerekméretű katicamintás pulóver. A tárgy, a maga kontrasztos motívumával azonnal felkeltette a figyelmemet. A kiállított tárgy mellett ez a szöveg olvasható: “Azoknak a zsidóknak, akiknek sikerült megszökniük a deportálások elől és 1944 őszén Szlovákiában maradtak, bujkálniuk kellett. Kisgyermekes családok az 1944-45-ös extrém telet erdőben, fűtetlen földalatti bunkerekben, kétségbeejtő higiéniai körülmények között, korlátozott élelmiszerellátás mellett töltötték. Pavel Traubner professzor, az ismert pozsonyi neurológus, a Szlovákiai Zsidó Hitközségek Központi Szövetségének tiszteletbeli elnöke volt az egyik ilyen gyermek. Évtizedek óta őrzi gyermekkori pulóverét emlékeztetőül a rejtőzködés reménytelen hónapjaira.” Saját művészeti praxisomban is sokszor foglalkozom régi tárgyakkal, sőt a magán életemben is gondosan elteszem a megörökölt dolgokat, emiatt könnyen tudok azonosulni a megőrzés gesztusával és a tárgyakon keresztül való emlékezéssel. Az eltelt évtizedek és a megváltozott társadalmi, történelmi kontextus miatt a tárgy, amely elvesztette eredeti funkcióját, új jelentésrétegekkel töltődik fel, és az emlékezet hordozójává válik.

Habár a rendszerváltás Szlovákiában Magyarországgal egy időben ment végbe, nem lehet figyelmen kívül hagyni azt az időben közeli és a rendszerváltás következményeként bekövetkezett radikális változást, amely 1993-ban Csehszlovákia szétválásához, vagyis az önálló Szlovák Köztársaság megalakulásához vezetett. Ez utóbbi esemény és az ezzel járó radikális nézetek hallatása a zsidó közösség tagjaiban érthető módon, a fasiszta Szlovák Állam (1939-1945) rémképét elevenítette fel. Szlovákiában a rendszerváltás időszakában a magyarországihoz képest lassabban alakultak ki a zsidó történelemmel foglalkozó intézmények.

Az, hogy ma a pulóver sorsa sok más történettel egyetemben megismerhető, egy hosszú folyamat eredménye. Munkám a rendszerváltást követő eseményekből emel ki néhányat, a pulóvert hordó és megőrző, a pulóver történetét feltáró és a pulóvert a Zsidó Közösségi Múzeumnak gyűjteményébe bevonó személyek megismertetésével. A pulóver replikájának létrehozásával, valamint a ruhadarab történetének egy új kontextusban, egy új közönség számára történő újramesélésével voltaképpen annak továbbírására teszek kísérletet.”

/ “Among the items on exhibit in the Jewish Community Museum in Bratislava is a child’s sweater with ladybug patterns. The object, with its dramatic motif, immediately caught my eye. Next to the sweater one finds the following text:

“Jews who managed to escape the deportations and remained in Slovakia in the autumn of 1944 were compelled to go into hiding. Families with young children spent the extreme winter of 1944–45 in the woods, in unheated underground bunkers, under dreadful hygienic conditions, and with only limited food supplies. Professor Pavel Traubner, a well-known neurologist from Bratislava and Honorary President of the Central Alliance of Jewish Communities in Slovakia, was one of these children. For decades, he has kept his childhood sweater as a reminder of the desperate months he spent in hiding.”

In my work as an artist, I often deal with old objects, and I myself also take care of things I have inherited, so I can easily identify with the gesture of preservation and memory through objects. As decades pass and the social and historical context changes, an object that has lost its original function acquires new layers of meaning and becomes a crucible of memory.

Although the fall of socialism in Slovakia happened at the same time as in Hungary, one cannot ignore the radical change that took place a few years later in no small part as a consequence of the regime change, which led to the breakup of Czechoslovakia in 1993 and the formation of the independent Slovak Republic. This latter event and the radical views it brought to the fore understandably evoked the horrifying image of the fascist Slovak State (1939–1945) among members of the Jewish community. During the period of regime change in Slovakia, institutions dealing with Jewish history emerged more slowly than in Hungary.

The fact that today we know the fate of the sweater and indeed the stories of many other objects is the result of a long process. My work calls attention to some of the events that followed the change of regimes, introducing the people who wore and preserved the sweater, who uncovered its history, and who made it part of the collection in the Jewish Community Museum. By creating a replica of the sweater and retelling the history of the garment in a new context for a new audience, I am in effect making an attempt to keep writing this story.”