papír, nyomat, 20×30 cm, 2015 / paper, print, 20×30 cm, 2015

1944 márciusában a Szabolcs utcai zsidó kórház épületeit és berendezéseit a megszálló hatóságok lefoglalták. Mivel az orvosoknak és a betegeknek távozniuk kellett, szükségkórházakat hoztak létre a Wesselényi utca 44-ben működő iskolában és a Bethlen tér 2. szám alatt, az Izraelita Siketnémák Országos Intézetének egykori épületében.

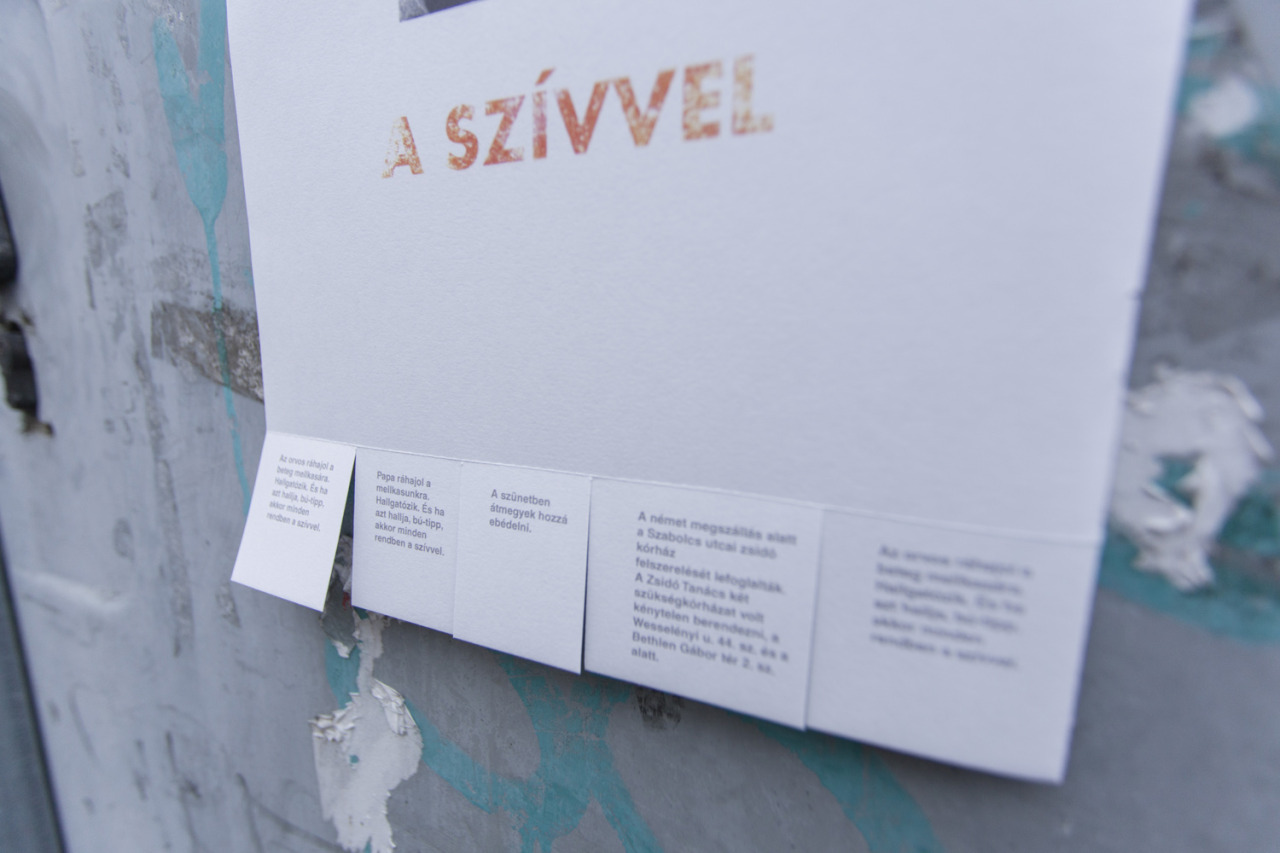

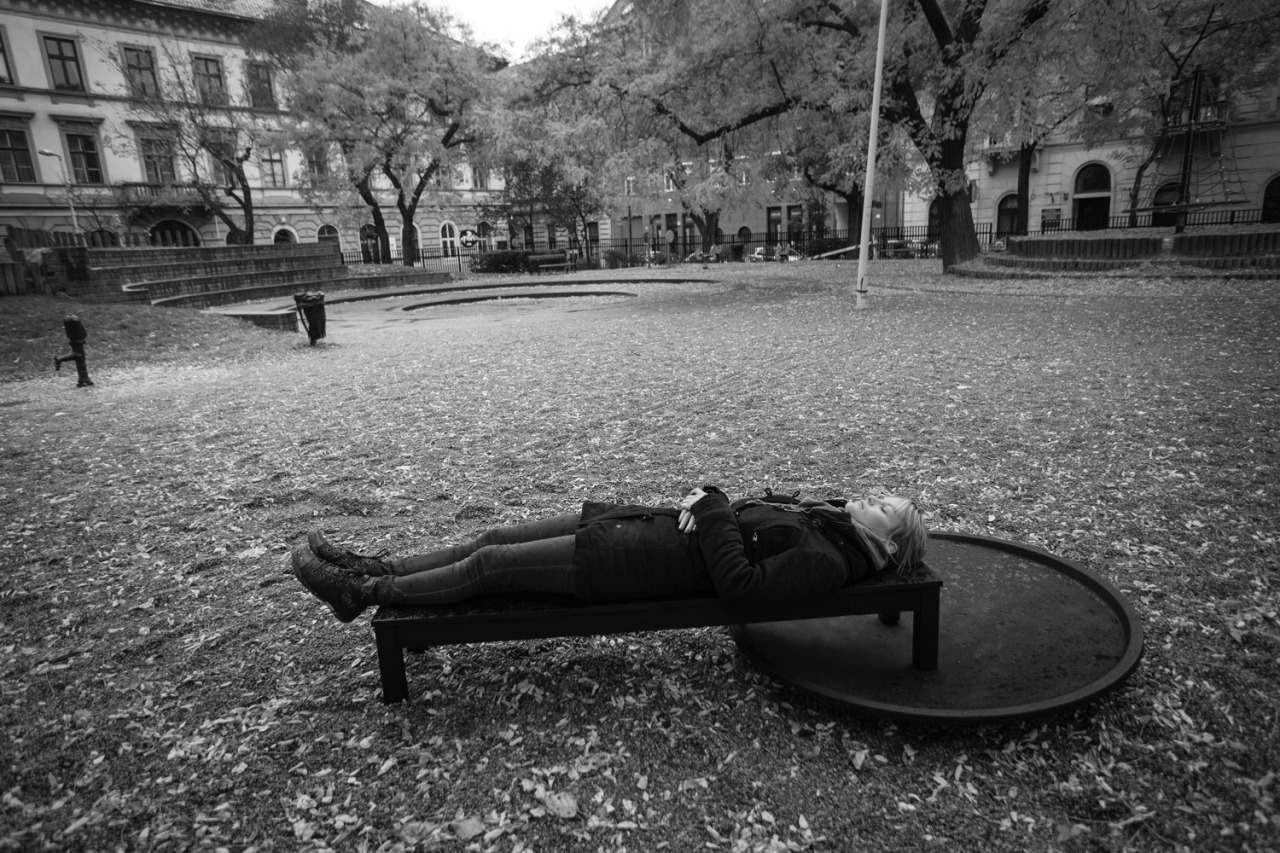

A Bethlen térre kihelyezett plakátokon a személyes és a történeti emlékek szövedékét akartam megmutatni. A letéphető, perforált lapokra egy-egy mondatot írtam. Ezek a mondatok hol a Bethlen térhez kötődő személyes emlékeimet, hol történeti tényeket közölnek. A személyes mondatok néhol szándékosan elszemélytelenítve, átfogalmazva jelennek meg a plakátokon.

(A felhasznált fotó forrása: Dr. Strausz Imre: Egy Zsidó Kórház 1944-ben, Emlékezésvázlat ötven év múltán című visszaemlékezéséből származik. Megjelent: Múlt és Jövő folyóirat, 1994. A fotó Dr. Lévy Lajos igazgatófőorvost ábrázolja 1938ban, amint egy betege fölé hajol.)

/ All the buildings and the equipment belonging to the Jewish hospital in Szabolcs Street were seized by the occupying authorities. As doctors and patients had to leave, casualty clearing stations were set up in the school building on 44 Wesselényi Street and at 2 Bethlen Square, the former residence of the Israelite Institute for the Deaf and Dumb.

Through a loose stream of posters hung along Bethlen Square I wanted to create a visible web of personal and historical memories. On the tear-off tabs of the posters I left one long sentence each. These sentences either echo my personal memories or recall historical facts, both in connection with Bethlen Square. The personal quotations were deliberately generalised in several cases.

Source of the photograph: Dr. Imre Strausz: Egy Zsidó Kórház 1944ben, Emlékezésvázlat ötven év múltán. The memoir of Strausz was published in the journal Múlt és Jövő in 1994. The photograph depicts the hospital director dr. Lajos Lévy, leaning over a patient.